Maria Bartiromo: An Advocacy Statement for Her USC Honorary Degree

At the

close of each academic term, universities across the world present members of their graduating classes with the degree for which their coursework has qualified them. During commencement ceremonies, others who have not gone through degree programs are also recognized by the university: recipients of honorary degrees. Bestowed upon individuals of various backgrounds and accomplishments, the practice of awarding honorary degrees is entwined in higher education and dates far back into its history. A former president of Dartmouth College, James Freedman, wrote in his book, Liberal Education and the Public Interest, that honorary degrees allow “a university [to make] an explicit statement to its students and the world about the qualities of character and attainment it admires most” (117). Like most universities, the University of Southern California engages itself annually in the custom. According to its website, USC’s purpose of bestowing such degrees is to “honor individuals who have distinguished themselves through extraordinary achievements in scholarship, the professions, or other creative activities, whether or not they are widely known by the general public.” Among the candidates for the honor this year should be business journalist Maria Bartiromo. Working in financial news for almost two decades, the excellence of Bartiromo’s reportage has earned her distinction beyond the scope of her job as a broadcast reporter for CNBC. Her reporting style has helped shape current coverage of business news in her immediate field and has also permeated into general journalism. In addition to her role as a leading contributor for today’s news format, Bartiromo deserves to be recognized at USC as a Doctor of Laws for her efforts to help the public. She synthesizes the often complicated numbers and presents the business issues she uncovers in ways that enables the individual investor to have access to the same caliber of information as major stock brokers.

close of each academic term, universities across the world present members of their graduating classes with the degree for which their coursework has qualified them. During commencement ceremonies, others who have not gone through degree programs are also recognized by the university: recipients of honorary degrees. Bestowed upon individuals of various backgrounds and accomplishments, the practice of awarding honorary degrees is entwined in higher education and dates far back into its history. A former president of Dartmouth College, James Freedman, wrote in his book, Liberal Education and the Public Interest, that honorary degrees allow “a university [to make] an explicit statement to its students and the world about the qualities of character and attainment it admires most” (117). Like most universities, the University of Southern California engages itself annually in the custom. According to its website, USC’s purpose of bestowing such degrees is to “honor individuals who have distinguished themselves through extraordinary achievements in scholarship, the professions, or other creative activities, whether or not they are widely known by the general public.” Among the candidates for the honor this year should be business journalist Maria Bartiromo. Working in financial news for almost two decades, the excellence of Bartiromo’s reportage has earned her distinction beyond the scope of her job as a broadcast reporter for CNBC. Her reporting style has helped shape current coverage of business news in her immediate field and has also permeated into general journalism. In addition to her role as a leading contributor for today’s news format, Bartiromo deserves to be recognized at USC as a Doctor of Laws for her efforts to help the public. She synthesizes the often complicated numbers and presents the business issues she uncovers in ways that enables the individual investor to have access to the same caliber of information as major stock brokers.Even in the recent past, USC has compromised the proclamations of its honorary degree criteria and its character by awarding such degrees to persons that were, at best, minimally qualified. In the last six years, the university’s website details 27 instances that such degrees were presented. The institution's decision to honor only four or five, sometimes even only two, persons indicates that there are few individuals it deemed worthy of the prestige of a doctoral level degree. The thought that the university regards degrees so preciously is soothing, but further examination of these individuals rais

es questions of whether or not they should have been awarded. Of the degrees given since 2000, seven were given to trustees or trustees’ spouses, three to high-ranking USC professionals, two to politicians in office at the time, and one to a generous donor. Freedman admits that universities have strayed from honoring individual achievements and have instead turned to their “desires to flatter generous donors and prospective benefactors to whom more relaxed standards…are typically applied” (126). Donors have been integral supports in USC's drive to become a leading national university; honoring these donors with degrees is one way in which administrators can ensure future funding. Although this process does facilitate considerable donations, it is still reprehensible that almost 50 percent of the 27 degrees were given because of the university's self-serving motivations. Current students, alumni and others should be outraged. In its Code of Ethics, which has been adopted by the trustees – including six of whom were recently honored – the university states, “We promptly and openly identify and disclose conflicts of interest on the part of…the institution as a whole.” Trustee recipients of the award are denoted, but the document does not explicitly state that Elaine Leventhal, a 2000 honorary degree holder, is the wife of trustee Kenneth Leventhal or that both the Leventhals and Andrew Viterbi, Robert Zemeckis, and Wallis Annenberg - others honored similarly by the university - donated enough money to have campus buildings named after them.

es questions of whether or not they should have been awarded. Of the degrees given since 2000, seven were given to trustees or trustees’ spouses, three to high-ranking USC professionals, two to politicians in office at the time, and one to a generous donor. Freedman admits that universities have strayed from honoring individual achievements and have instead turned to their “desires to flatter generous donors and prospective benefactors to whom more relaxed standards…are typically applied” (126). Donors have been integral supports in USC's drive to become a leading national university; honoring these donors with degrees is one way in which administrators can ensure future funding. Although this process does facilitate considerable donations, it is still reprehensible that almost 50 percent of the 27 degrees were given because of the university's self-serving motivations. Current students, alumni and others should be outraged. In its Code of Ethics, which has been adopted by the trustees – including six of whom were recently honored – the university states, “We promptly and openly identify and disclose conflicts of interest on the part of…the institution as a whole.” Trustee recipients of the award are denoted, but the document does not explicitly state that Elaine Leventhal, a 2000 honorary degree holder, is the wife of trustee Kenneth Leventhal or that both the Leventhals and Andrew Viterbi, Robert Zemeckis, and Wallis Annenberg - others honored similarly by the university - donated enough money to have campus buildings named after them.While the university, as a private institution, is free to honor whomever it wants for whatever reasons it decides, members of the Honorary Degree Committee need to realize that presenting so many degrees to individuals that have financial and political connections to USC welcomes scrutiny. The university goes on in the Code of Ethics to say that it will “take appropriate steps to either eliminate such conflicts [of interest] or insure that they do not compromise the integrity of the individuals involved…” Although it would not be reasonable to expect the university to strip honorary degrees from its closest affiliates, the degree-granting committee should take less direction from the university’s administration and draw more upon other sources for recommendations. Since the committee is comprised largely of faculty members of various fields, the members’ colleagues and others they are acquainted with in academia would serve as excellent degree candidates. Interest groups made up of students, alumni and faculty members not represented by the committee would also generate appropriately qualified nominees. A coalition of these groups’ strong voices and the committee's support would effectively find the candidates the university claims it wishes to honor. In addition to consulting with interests on campus, the selection committee would do well to desist from honoring individuals that fit only the “Doctor of Humane Letters” designation, which generalizes candidates' accomplishments, denoting them an "outstanding citizen." The university should return to the practice of honoring persons in recognition of distinctions in science, literature, music, fine arts, and divinity, as well as award candidates of the laws category, which acknowledges persons that engage in outstanding public service.

The selection of Bartiromo for a degree would help alleviate the university’s propensity for abusing the tradition of awarding honorary degrees. There are many reasons for her candidacy. Beginning with professional esteem, Bartiromo is a model that many journalists should follow. Especially in the field of business journalism

where journalists face practices that companies use in the intent to sway coverage in their favor, it can be difficult to maintain an ethical stance. Not only has Bartiromo managed to keep away from the temptations that have assuredly presented themselves in the course of her career working for major news outlets, but she has positioned herself as a leader in reporting on the financial markets. She had been employed by CNN Business News since she graduated from New York University as a journalism major and economics minor. Now reporting for CNBC, MSNBC and NBC’s Today Show, she has continued to work for leading organizations. The excellence of her hard-hitting accounts has also propelled Bartiromo into the competing realm of print journalism: she writes regular columns on money and finance for Reader’s Digest Magazine and Business Week.

where journalists face practices that companies use in the intent to sway coverage in their favor, it can be difficult to maintain an ethical stance. Not only has Bartiromo managed to keep away from the temptations that have assuredly presented themselves in the course of her career working for major news outlets, but she has positioned herself as a leader in reporting on the financial markets. She had been employed by CNN Business News since she graduated from New York University as a journalism major and economics minor. Now reporting for CNBC, MSNBC and NBC’s Today Show, she has continued to work for leading organizations. The excellence of her hard-hitting accounts has also propelled Bartiromo into the competing realm of print journalism: she writes regular columns on money and finance for Reader’s Digest Magazine and Business Week.Part of what keeps Bartiromo in the public spotlight has nothing to do with her reporting skills or substantial knowledge of the markets; some attribution of her status is due to good looks. Dubbed the “Money Honey” and “Econo Babe” by market players and fans, Bartiromo’s career arguably took off not when she began broadcasting the news, but the day when sh

e became the first person to report from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in 1995. The juxtaposition of an attractive, Sophia-Loren-looking reporter against the backdrop of so many men in banal suits was explosive. The success of that shot, which CNBC continued to make for ten years afterward, sparked her career and simultaneously set her apart from the other women who were reporting the markets at the time. At USC, where one of the honorary degree recipients delivers the commencement address, Bartiromo's celebrity status would not go unappreciated. As a person who works daily on the air, she speaks effectively. Experience on various panels and speeches at conference summits further qualify her bid. The content of Bartiromo’s address might draw upon two of the pillars of her success: personalization of financial news and truthful analysis. Since this reporter is a strong advocate of the average person making investments, she would offer graduating students tips on how they might best manage their finances and pay off the loans that will be pending after the very conclusion of graduation ceremonies. In what is a signature style, she would be able to explain how the markets are operating and why, then relate the effects to the individual. Students would be certain that what she said was accurate because of her reputation for talking extensively with big market players and the ability to sort out the truth from their testimonies. In her book, Use the News: How to Separate the Noise from the Investment Nuggets and Make Money in any Economy, Bartiromo states her role in deciding amongst many sources of information what is important. She says, "...I would like to think of myself as a gatekeeper, because I make the distinction between news and noise" (193).

e became the first person to report from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in 1995. The juxtaposition of an attractive, Sophia-Loren-looking reporter against the backdrop of so many men in banal suits was explosive. The success of that shot, which CNBC continued to make for ten years afterward, sparked her career and simultaneously set her apart from the other women who were reporting the markets at the time. At USC, where one of the honorary degree recipients delivers the commencement address, Bartiromo's celebrity status would not go unappreciated. As a person who works daily on the air, she speaks effectively. Experience on various panels and speeches at conference summits further qualify her bid. The content of Bartiromo’s address might draw upon two of the pillars of her success: personalization of financial news and truthful analysis. Since this reporter is a strong advocate of the average person making investments, she would offer graduating students tips on how they might best manage their finances and pay off the loans that will be pending after the very conclusion of graduation ceremonies. In what is a signature style, she would be able to explain how the markets are operating and why, then relate the effects to the individual. Students would be certain that what she said was accurate because of her reputation for talking extensively with big market players and the ability to sort out the truth from their testimonies. In her book, Use the News: How to Separate the Noise from the Investment Nuggets and Make Money in any Economy, Bartiromo states her role in deciding amongst many sources of information what is important. She says, "...I would like to think of myself as a gatekeeper, because I make the distinction between news and noise" (193).Her celebrity status might be the deterrent that keeps the Honorary Degree Committee from selecting Bartiromo for the honorary degree, however. In contemporary society, degrees from prestigious institutions have become the social accessories that ensure prominent status. Universi

ties have bestowed their highest honors on famous persons in the past, augmenting the use of degrees as a fashion accessory. Perhaps to secure the best-known, most popular speaker at their commencement ceremony, Freedman suggests that colleges seek to flatter celebrities or even pay personalities in upwards of $10,000 to speak (128). USC has featured notable people in three past commencement addresses: Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, astronaut Neil Armstrong, and Senator John McCain. The university has avoided criticism by not honoring music or film stars in its recent history, but its 2001 decision to bestow former J. Paul Getty Trust president Barry Munitz, well-known to those at all familiar with art organizations, is a move it certainly regrets. USC President Steven Sample’s resignation as a Getty Trustee in March 2005 was a probable indication of the university’s embarrassment of Munitz’ forced resignation from his position in February 2006. Munitz had to resign due to his mismanagement of Getty money and because of the culture he created at the musuem, which was swirling in investigations surrounding its alleged participation in the buying of stolen artworks. The university was probably further dismayed when it was reported that Cal State University (CSU) faculty drafted an unauthorized resume detailing their views of Munitz’ professional career and protest to his hire as a “trustee professor” at CSU through a discontinued program.

ties have bestowed their highest honors on famous persons in the past, augmenting the use of degrees as a fashion accessory. Perhaps to secure the best-known, most popular speaker at their commencement ceremony, Freedman suggests that colleges seek to flatter celebrities or even pay personalities in upwards of $10,000 to speak (128). USC has featured notable people in three past commencement addresses: Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, astronaut Neil Armstrong, and Senator John McCain. The university has avoided criticism by not honoring music or film stars in its recent history, but its 2001 decision to bestow former J. Paul Getty Trust president Barry Munitz, well-known to those at all familiar with art organizations, is a move it certainly regrets. USC President Steven Sample’s resignation as a Getty Trustee in March 2005 was a probable indication of the university’s embarrassment of Munitz’ forced resignation from his position in February 2006. Munitz had to resign due to his mismanagement of Getty money and because of the culture he created at the musuem, which was swirling in investigations surrounding its alleged participation in the buying of stolen artworks. The university was probably further dismayed when it was reported that Cal State University (CSU) faculty drafted an unauthorized resume detailing their views of Munitz’ professional career and protest to his hire as a “trustee professor” at CSU through a discontinued program.This recent scandal may prompt the committee to disregard Bartiromo from an award, but unlike Munitz’ power or other celebrities’ fame, it is Bartiromo’s skill that s

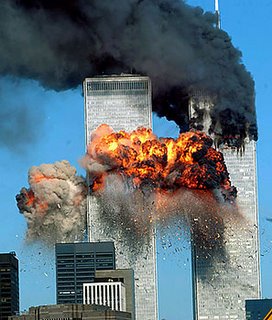

ubstantiates her celebrity status. An example of her excellent reportage comes through her nomination for the 2001 Gerald Loeb Award for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism for her piece on the widows of September 11. For this package, she interviewed Cantor Fitzgerald CEO Howard Lutnick after the New York terrorism attacks left 700 of his employees dead. Lutnick had told widows of those employees that Cantor would continue to help them when he was interviewed on national television. Cantor stopped paying the 700 missing employees’ salaries even as firefighters continued to search for them. After interviewing some of those widows about their predicament, Bartiromo asked Lutnick the hard question: How would he protect these widows like he promised when his company cut-off their financial support? Arguably, Bartiromo’s report encouraged the company to establish the Cantor Relief Fund, which provides “direct assistance to those who lost loved ones in the tragedy” and the Cantor Families Memorial, a collection of online memorials to the employees that died as a result of the attacks.

ubstantiates her celebrity status. An example of her excellent reportage comes through her nomination for the 2001 Gerald Loeb Award for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism for her piece on the widows of September 11. For this package, she interviewed Cantor Fitzgerald CEO Howard Lutnick after the New York terrorism attacks left 700 of his employees dead. Lutnick had told widows of those employees that Cantor would continue to help them when he was interviewed on national television. Cantor stopped paying the 700 missing employees’ salaries even as firefighters continued to search for them. After interviewing some of those widows about their predicament, Bartiromo asked Lutnick the hard question: How would he protect these widows like he promised when his company cut-off their financial support? Arguably, Bartiromo’s report encouraged the company to establish the Cantor Relief Fund, which provides “direct assistance to those who lost loved ones in the tragedy” and the Cantor Families Memorial, a collection of online memorials to the employees that died as a result of the attacks.Although Bartiromo's formal business training is limited to the courses she took for an economics minor, this reporter knows financial news well because she is constantly asking market players – major or not – about it. Each morning and afternoon in the past, Bartiromo has prepped for her spots on CNBC shows by calling brokers and hedge fund managers, reading stories and studying reports. She does not shy from asking the top executives she exclusively interviews about pressing issues. Bartiromo has modified the shows she reports for, but not her strategy for asking questions. Her propensity for digging for information has led to controversy in the past. While she dined on invita

tion at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in late April 2006, she spoke with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, who was in attendance. In an attempt to learn whether the financial world interpreted remarks he made that the Fed was finished raising interest rates correctly or not, Bartiromo said she "asked him whether the markets got it right after his congressional testimony and he said, flatly, no.” After reporting this news on the air, investors quickly reacted and the markets took a hit, leaving ethical questions for Bartiromo. An enraged John Berry, who had been a seasoned Federal Reserve columnist for the Washington Post until he took a similar position with Bloomberg News, slammed her in his column, writing that she “badly burned” Bernanke. Blogger Barry Ritholtz, a strategist for an institutional research firm whose blog has over seven million hits, synthesized that Berry was accusing Bartiromo of “not understanding the rules of engagement when mixing at social functions with the personalities and subjects they cover.” In follow-up coverage, most articles covered the story from the perspective that the Fed chairman should have exercised more caution when talking to a journalist and chided him for being “dovish” on comments that led investors astray. Bartiromo sensed correctly that Bernanke was not being forthright at the hearings. Since the majority of the articles faulted Bernanke, it is reasonable to surmise that most of the reporters sided with Bartiromo and believed almost all comments made to a journalist, wherever the location, are inherently on-the-record rather than off-record.

tion at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in late April 2006, she spoke with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, who was in attendance. In an attempt to learn whether the financial world interpreted remarks he made that the Fed was finished raising interest rates correctly or not, Bartiromo said she "asked him whether the markets got it right after his congressional testimony and he said, flatly, no.” After reporting this news on the air, investors quickly reacted and the markets took a hit, leaving ethical questions for Bartiromo. An enraged John Berry, who had been a seasoned Federal Reserve columnist for the Washington Post until he took a similar position with Bloomberg News, slammed her in his column, writing that she “badly burned” Bernanke. Blogger Barry Ritholtz, a strategist for an institutional research firm whose blog has over seven million hits, synthesized that Berry was accusing Bartiromo of “not understanding the rules of engagement when mixing at social functions with the personalities and subjects they cover.” In follow-up coverage, most articles covered the story from the perspective that the Fed chairman should have exercised more caution when talking to a journalist and chided him for being “dovish” on comments that led investors astray. Bartiromo sensed correctly that Bernanke was not being forthright at the hearings. Since the majority of the articles faulted Bernanke, it is reasonable to surmise that most of the reporters sided with Bartiromo and believed almost all comments made to a journalist, wherever the location, are inherently on-the-record rather than off-record. USC should embrace the Bernanke controversy as an illustration of Bartiromo’s dedication for repor

ting the news. In Use the News, she describes how much she loves her job. "I zero in on exactly what I need to do now, namely, deliver the news....I give my audio guy his ten-count without thinking and I get to work. I have been called a multi-tasker, and I find it's not that difficult to do with a little focus" (31), Bartiromo says. Her drive to work market sources at every chance shows clearly shows this dedication. Mike Martin criticizes Adam Smith’s concept of the invisible hand, where a force equalizes merchant and consumer demands into an equilibrium in the book, Meaningful Work: Rethinking Professional Ethics (12). He writes that the free market is a haphazard regulator “unless the majority of professionals are committed in ways that merit public trust” (15). Part of Bartiromo’s drive comes from wanting to get the news right, but a larger portion comes from this aspiration to inform the public. If Bartiromo had asked Bernanke what she did and not reported it, the markets would have gone on operating with the wrong assumptions. With a wider application of USC’s Role and Mission statement that states its faculty are “contributors of what is taught, thought and practiced throughout our world,” Bartiromo’s actions would be pleasing to the university and its community.

ting the news. In Use the News, she describes how much she loves her job. "I zero in on exactly what I need to do now, namely, deliver the news....I give my audio guy his ten-count without thinking and I get to work. I have been called a multi-tasker, and I find it's not that difficult to do with a little focus" (31), Bartiromo says. Her drive to work market sources at every chance shows clearly shows this dedication. Mike Martin criticizes Adam Smith’s concept of the invisible hand, where a force equalizes merchant and consumer demands into an equilibrium in the book, Meaningful Work: Rethinking Professional Ethics (12). He writes that the free market is a haphazard regulator “unless the majority of professionals are committed in ways that merit public trust” (15). Part of Bartiromo’s drive comes from wanting to get the news right, but a larger portion comes from this aspiration to inform the public. If Bartiromo had asked Bernanke what she did and not reported it, the markets would have gone on operating with the wrong assumptions. With a wider application of USC’s Role and Mission statement that states its faculty are “contributors of what is taught, thought and practiced throughout our world,” Bartiromo’s actions would be pleasing to the university and its community.The university asserts its diligence to keep distant from conflicts of interest on the honorary degrees website, but as already discussed, has had troubles enacting that goal. The institution could look to Bartiromo as an exemplar in this respect. Like other business reporters who are often privledged to financial information before it is released publicly, Bartiromo would be governed by strict rules if she traded stocks because of Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) insider trading concerns. Reporters are legally permitted to invest and trade stocks, but Bartiromo restricts herself more acutely than either the SEC or CNBC does: she does not own shares at all. In her book, she "concluded that the best way to handle any confusion about [her] agenda was to not trade at all" (194). Although stock ownership is allowable if pertinent disclosure rules are followed, Bartiromo decides to circumvent any controversy, reasoning that her position and owning stocks "do not go hand-in-hand" (194). Martin notes that some hold the view that "moral ideals should essentially be relegated to private life, with professional life guided primarily by economic and self-interested values together with minimal moral restrictions" (12). With the information she receives, Bartiromo would be poised to add much wealth to her portfolio, but she cements her private life with her professional career and finds them to be inseparable. Bartiromo is unlike the professional Martin says the Wealth of Nations emphasizes, that which defines professionals as "driven by self-interest and not by moral values of caring about helping people" (13). Instead, she cements her private life with a professional career and finds them to be inseparable.

Since USC will continue to bestow honorary degrees upon individuals, awarding Bartiromo a degree would best serv

e the interests of itself and those it impacts. On the honorary degree site, USC says it is "particularly interested in candidates...whose own accomplishments might serve to highlight areas in which the University has developed exceptional strength." Recognizing that the degree awarding process should undergo changes because of questionable past recipients, one way the university could work to reform selections is to extend this interest to candidates who have excelled in ways it has not. Bartiromo has taken preventative action to ensure she does not pollute public information with personal biases. Learning from her, USC could safe-guard the prestige of the honorary degree program by not weighting the candidacy of donors and others close to the insitution. While the blemishes that have already been imprinted onto the program’s record will remain there, USC administrators can work to improve the strength and restore the prestige of honorary degrees if it again evaluates the criteria that has already been outlined and realizes that many past recipients were not qualified candidates. When the Honorary Degree Committee realizes this, it will also be clear that persons like Bartiromo, who have accomplished much in their fields and are poised to do even more, are most deserving of the university’s highest honor.

e the interests of itself and those it impacts. On the honorary degree site, USC says it is "particularly interested in candidates...whose own accomplishments might serve to highlight areas in which the University has developed exceptional strength." Recognizing that the degree awarding process should undergo changes because of questionable past recipients, one way the university could work to reform selections is to extend this interest to candidates who have excelled in ways it has not. Bartiromo has taken preventative action to ensure she does not pollute public information with personal biases. Learning from her, USC could safe-guard the prestige of the honorary degree program by not weighting the candidacy of donors and others close to the insitution. While the blemishes that have already been imprinted onto the program’s record will remain there, USC administrators can work to improve the strength and restore the prestige of honorary degrees if it again evaluates the criteria that has already been outlined and realizes that many past recipients were not qualified candidates. When the Honorary Degree Committee realizes this, it will also be clear that persons like Bartiromo, who have accomplished much in their fields and are poised to do even more, are most deserving of the university’s highest honor.